By Jeff Burbank

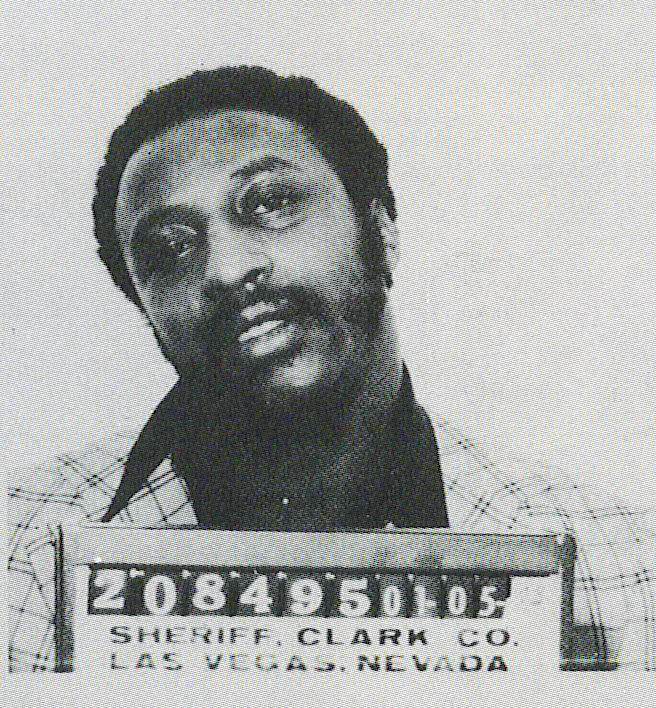

It was the first week of January 1973. Frank Matthews and his young girlfriend had just spent the holidays in Las Vegas and were about to board a flight to Los Angeles. In the previous several years, Matthews had made many trips to Las Vegas, carrying suitcases full of cash to be secretly laundered at casinos for a fee of 15 to 18 percent. This time, federal drug enforcement agents were waiting and placed him and the woman under arrest at McCarran International Airport.

Two weeks before, U.S. prosecutors in Brooklyn, New York, had issued an arrest warrant for Matthews, the top black drug kingpin in America whose heroin and cocaine trafficking gang of mostly African-American dealers extended to 21 states on the Eastern Seaboard. He was charged with trying to sell about 40 pounds of cocaine in Miami from April to September 1972, a small fraction of the drugs he’d pushed since 1968.

The feds believed Matthews had millions in currency stashed away in safety deposit boxes in Las Vegas. They wanted him in jail until they could have him extradited back to Brooklyn. A sympathetic federal magistrate in Las Vegas set bail for Matthews at $5 million, the highest bail amount at the time in U.S. history. On his way out of court, an IRS agent informed Matthews he owed back taxes on $100 million the drug dealer had earned in 1971 alone.

But that wasn’t quite the end of the story. Matthews’ life remains a mystery to this day. Let out in April 1973 on a mere $325,000 bail after serving four months in jail in New York, the 29-year-old Matthews failed to show for a hearing in Brooklyn on a list of felony charges that July. He and his girlfriend Cheryl Denise Brown had vanished. A friend reported that Matthews and Brown took a flight to Houston. Some authorities believe he left with as much as $20 million in laundered cash. A month later, IRS agents, acting on a tip, rushed to a bank in North Carolina. “Oh, you just missed him,” the manager told them.

No trace of Matthews (or Brown) has been found since – no fingerprints, no sightings, no confirmed leads, no recorded contacts with family members. In 1974, the newly formed Drug Enforcement Agency offered a $20,000 reward for information leading to his arrest, then the biggest reward since the one for Depression-era gangster John Dillinger in 1931. Matthews has been compared to Mob boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar, so skilled was he in the transportation, manufacturing and selling of large amounts of heroin and cocaine, as well as security and money laundering.

The story of how Matthews created a drug empire almost without detection by law enforcement for years while openly defying – and cutting out — New York’s “white” organized crime families is told by author Ron Chepesiuk in his book, Black Caesar: The Rise and Disappearance of Frank Matthews, Kingpin. Chepesiuk spoke at The Mob Museum about his book on Saturday, Feb. 6.

Matthews, born in 1944 in the segregated town of Durham, North Carolina, trained as a barber, drifted to Philadelphia and then to New York in the early 1960s. He earned himself a place in the city’s numbers racket from inside a barbershop and came in contact with underworld figures. Into the mid-1960s, New York’s five Italian crime families and some Jewish underworld figures kept a grip on drug dealing – specifically heroin — in the city’s black neighborhood, Harlem. One black dealer who worked with the “white” mob was the famous gangster Bumpy Johnson, who died in 1968. But by then, independent African-American gangsters started coming into the drug scene.

In the mid-1960s, the Mafia’s famed French Connection of heroin trafficking was still going strong. The Mafia ran the connection by exporting morphine base from opium poppies in Turkey and refining the product in Marseilles, France, where Corsican drug sellers sent the heroin to New York for street sales. It was through the Corsicans that Matthews would later enter the illegal drug trade and rise to become a major dealer.

At first Matthews felt he had to prove himself with New York’s crime groups. He sought the attention of the Gambinos and Bonannos, but they refused to allow him in. Through the numbers racket he met Spanish Raymond Marquez, one of New York’s major numbers operators who introduced Matthews to a Cuban friend, Roland Gonzalez, one of the town’s main drug dealers. Gonzalez had him do some narcotics deals and the two became friends.

When Gonzalez fled to Venezuela to avoid a drug trafficking charge in 1969, he helped set up Matthews back in the States. Gonzalez, working with the Corsicans, became Matthews’ supplier for heroin and cocaine from Latin America, propelling Matthews into the big time. While U.S. authorities were well aware of Gonzalez, for some reason Matthews remained unknown to them for years.

Matthews disliked the Italian crime families and avoided working with them, with the exception of Louis Cirillo, to whom the families entrusted New York’s heroin racket. Through supplies furnished by Gonzales and Cirillo, Matthews, shrewd and brilliant, evolved into New York’s premiere narcotics dealer.

By the early 1970s, his drug empire stretched to 21 states, from Boston to Connecticut to the Midwest, as far south as Alabama and as far west as Missouri. Matthews insisted on working with only African-Americans and some Hispanics as his underbosses. He was making as much as $250,000 in cash per deal. From 1969 to early 1970, he moved 100 to 150 kilos of heroin into New York. In 1971 he brashly held a meeting for his dealers in Atlanta to discuss business, and in 1972 chaired another such conclave in Las Vegas.

But things began to unravel for Matthews in the early 1970s, thanks to a neighbor of his in Brooklyn who was a New York City police detective. The detective grew suspicious while observing Matthews driving luxury cars and being visited day and night by men carrying paper bags. Checks of vehicle license numbers showed some were known drug dealers, although there was nothing solid on Matthews.

Finally, in June 1972, after Matthews’ dealers meeting in Las Vegas, police received permission to tap his phone. He was preparing to move into a large house in an upper-crust neighborhood on Staten Island with his wife and three kids. Authorities learned he was paying airline stewardesses $1,000 a month to smuggle heroin in their flight bags to airport lockers. By then, Matthews was importing cocaine from the Corsicans in Caracas, Venezuela, to his Cuban connection, George Ramos, in Miami. Matthews made some careless remarks over the phone and nine people were arrested, including Ramos in November 1972. Ramos ratted him out in front of a federal grand jury and later entered witness protection. In December, the federal arrest warrant was issued to deliver Matthews.

The law also caught up to Matthews’ gangsters. In February 1975, 18 members of what the New York Daily News described as a “black narcotics ring” on the East Coast were indicted by a federal grand jury, 12 of whom were already serving time for other crimes.

A drug dealer told police that once while visiting Matthews’ New York home to pay him, Matthews told him to put the cash in a nearby closet. The closet, the dealer claimed, was packed to eye level with stacks of money.

Some believe Matthews, who would be 71 years old today, may still be alive. One source heard he fled to the Bahamas, but no trace of him was found after a federal investigation. Some friends heard he was in Africa, others that he was killed by gangsters. A former member of the U.S. Marshals Service who handled his case thinks he is dead. The author Ron Chepesiuk also thinks it’s likely that Matthews has died but just what happened to him may never be known.

Comments

Post a Comment